What We're Really Consuming When We Watch What They Eat

The last mince pie has been eaten, the Christmas tree has been taken down, and we are moving from the weird in-between space of the holidays straight into the annual optimisation frenzy. New Year, New You. The resolutions, the diets (or GLP-1s), the gym memberships.

As we move from indulgence to optimisation, our social media feeds start shifting and the algorithm starts serving you “What I Eat in a Day” videos – or WIEIAD in internet shorthand. You may not have searched for them, but suddenly you are watching strangers eat. And the format is simple: first a quick body check before moving to a sequence of three meticulously plated meals, alongside some healthy snacks and a fancy drink. The subtext screams “eat like me, look like me”. But what we’re actually consuming is far more than just digital calories.

The Semiotics of the Square Meal

In the early days of Instagram, we laughed about anyone who uploaded a picture of their lunch “who wants to see what you’re eating?” Now? Videos with the hashtag #WhatIEatInADay have billions of views on TikTok.

When you’re capturing your meal on video or as a photo, you’re not just capturing food. You’re communicating more than what’s on your plate. Charles Peirce’s semiotic framework helps us understand this. A photo of a bowl of ramen becomes more once you add context: a geotag shows that you’re at a trendy pop-up place that you queued an hour to get in, a caption explaining the ingredients’ provenance. Each layer adds more and more specificity and transforms the mundane into something more meaningful.

French theorist Jean Baudrillard identified four stages of simulation, essentially a process through which images gradually detach from reality, until they become what he called “hyperreal” and as a result, the image no longer bears any relation to reality. WIEIAD content lives squarely in this territory. The aesthetically styled smoothie bowl, with its bright colours and geometrically arranged fruits, nuts and seeds doesn’t exist to be eaten. It exists to be photographed, filtered, posted, and admired. And in the admiration, this hyperreal image can never satisfy hunger, but only create more wanting.

Lifestyle Videos and the Theatre of Wellness

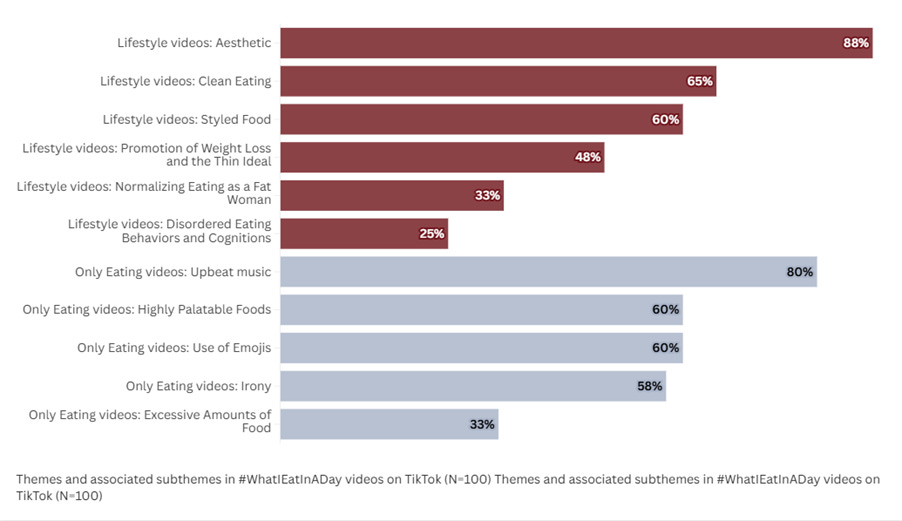

A 2023 study published in ‘Eating Behaviors’ analysed 100 highly-viewed WIEIAD videos and identified two distinct categories, which the researchers labelled either “Lifestyle” and “Only Eating”. The differences between them tell us about class, aspiration and the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

60% of the sample fell into the Lifestyle category. These were food videos with an elaborate performances of a certain kind of life. They all have a curated aesthetic: soft background music, beauty filters that smooth skin, matching dishes and neutral-coloured décor. This is designed to communicate: I have time, I have taste, I have control.

Clean eating featured in 65% of these videos. Water was featured prominently and discussed as if it was a moral virtue rather than a biological necessity. Nothing can be just consumed., it must be explained, defended, positioned within the current, dominant narrative of wellness.

The styled food subtheme appeared in 60% of the Lifestyle videos. As food scholar Adrienne Lehrer noted, this “luxury of time” communicates class status more effectively than any price tag could: the time to chop, to arrange, to photograph, to caption, to post.

What is most troubling, is that nearly half of these Lifestyle videos explicitly promoted weight loss and the thin ideal. You see creators stepping on scales, calorie counts are displayed, often totalling less than 1,500 across an entire day. The majority of these creators were thin, white, feminine-presenting women. Eating disorder content appeared in 25% of Lifestyle videos, including discussions of binge eating, laxative misuse, meal skipping, and restrictive behaviours.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

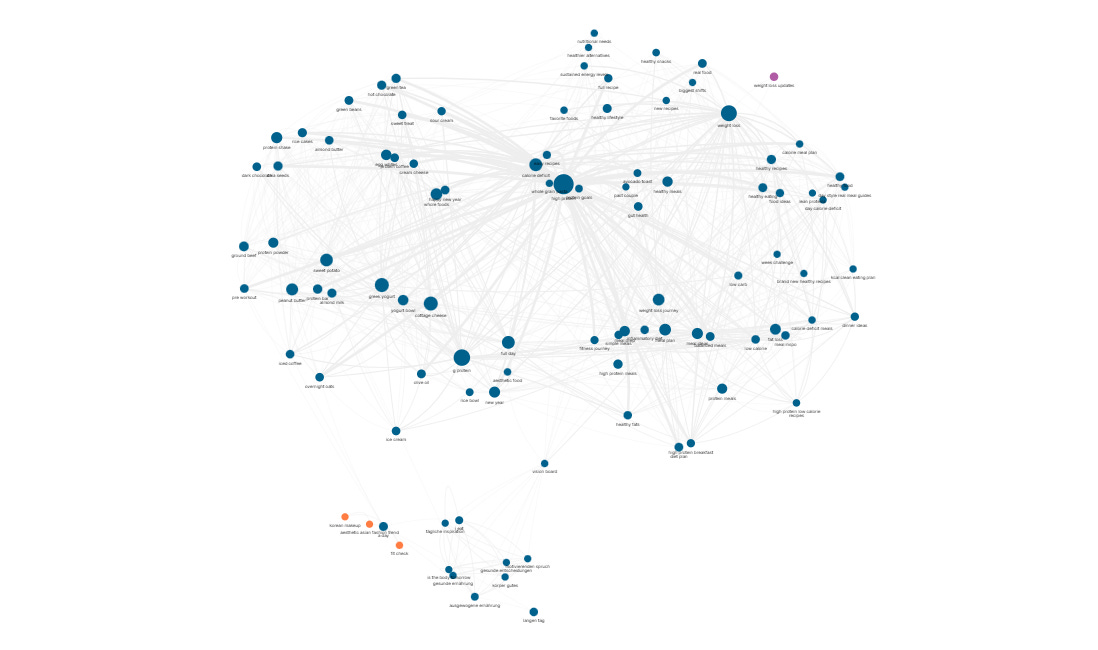

Recent social listening data from YouScan confirms that high-protein foods and calorie deficit strategies dominate the conversation. But when you look closer, you notice that niche items like olive oil, chia seeds, and green tea are mentioned consistently in unique contexts rather than repeatedly by the same voices.. More surprisingly, items like sour cream and hot chocolate frequently occur frequently in the same conversations as high protein, suggesting a mix of indulgence and healthy eating. This shows that WIEIAD videos is not be just about either deprivation or indulgence. It’s about the performance of balance, the aesthetic of having it both ways.

Only Eating and the Ironic Feast

The remaining 40% of videos fell into the “Only Eating” category. Here you do not see any filters or styled kitchens. It’s just food, and often, excessive amounts of it. The food skewed heavily towards fast food: fries, crisps, sweets, multiple slices of pizza consumed in quick succession.

However, 23 out of 40 of the videos in the sample seemed to be ironic. They were parodies of the Lifestyle videos, showing deliberately messy eating styles. Those creators filmed themselves chewing with mouths full, food falling out as they narrated what they ate. The irony functioned as both critique and protection. By presenting themselves as the opposite of the polished Lifestyle creators, they reject the impossible standards of wellness culture. But many of them also showed their thin bodies in full-length and some even weighed themselves to show that they hadn’t gained weight despite consuming massive quantities of food. The message underneath the irony is that “I can eat whatever I want and still look like this.”

The Absence That Creates the Appetite

Roland Barthes wrote that photography’s essence is “to ratify what it represents”, to confirm its presence. But food photography on social media doesn’t just confirm its presence, it also shows its absence for anyone viewing it. You can see the meal, but you cannot taste it or smell it. The photograph becomes what Barthes called “absence-as-presence”. WIEIAD content operates the same way. You scroll through your feed, watching stranger after stranger document their meals, and suddenly you’re aware of everything you’re not eating. The algorithm learns what makes you linger and serves you more of it

People don’t wait in an hour-long queue at a pop-up restaurant because they’re hungry. They wait because they need the proof of participation in a shared cultural moment. The actual eating becomes secondary to the digital consumption. This is what writer Jacob Silverman calls “the populist mantra of the social networking age”: pics or it didn’t happen. The experience must be documented to be validated, shared to be real.

The Class Question We’re Not Asking

There’s a reason most WIEIAD creators are white, thin, feminine-presenting women. There’s a reason the videos overwhelmingly feature either clean eating aesthetics or ironic excess. There’s a reason we’re not seeing content from people genuinely struggling with food insecurity.

The act of photographing food assumes your basic needs are met. It assumes access to smartphones, internet, and enough food that you can afford to style it, light it, potentially waste it in the pursuit of the perfect shot.

This absence of eating out of necessity or purely to survive isn’t accidental. Instagram and TikTok are fundamentally aspirational platforms. Food insecurity doesn’t fit into that and neither do the hearty, less photogenic meals that people cook when genuinely hungry.

What We’re Actually Hungry For

WIEIAD videos are problematic. They promote restrictive eating, unrealistic standards, and class exclusion. So why can’t we stop watching them?

Over a third of TikTok users in the United States are between 10 and 19 years old. They’re at an age where identity formation is in progress and the question “who am I?” feels urgent and uncertain. WIEIAD content answers that question. Not necessarily helpful answers, but answers nonetheless. Watch enough Lifestyle videos and you learn the visual grammar of wellness culture. Replicate these symbols and you signal membership in a community that values health, discipline, aesthetics. Watch enough Only Eating videos and you learn a different grammar: one of abundance, indulgence, the ironic rejection of restriction. Both grammars promise belonging.

If you watch one WIEIAD video, the algorithm serves you another. And another. If you lingered on the Lifestyle videos, you’ll see more of those. If you engaged with the Only Eating content, the algorithm learns to show you increasingly extreme examples. The personalisation feels intimate, almost uncanny. The platform appears to understand what you want before you fully understand it yourself.

This algorithmic curation makes WIEIAD content particularly potent for vulnerable viewers. The algorithm doesn’t distinguish between healthy interest and disordered fixation. It simply gives you more of what holds your attention. The comparison becomes inescapable. “I don’t eat like that.” “I should eat like that.” “If only I ate that way...” The thought patterns spiral, reinforced by each new video the algorithm serves up.

Even body-positive content can have paradoxical effects. 20 of the 60 Lifestyle videos in the sample featured creators using words like “fat”, “chunky” or “overweight” to describe themselves in neutral or affirming ways, often explicitly rejecting diet culture. But even positive body-focused commentary can increase self-objectification and appearance comparison.

The Monoculture We’ve Lost and Found Again

There’s something nostalgic about WIEIAD videos, although it took me a while to identify why. They offer a peculiar kind of intimacy, a simulation of closeness. This connects to a broader cultural longing for the monoculture we’ve supposedly lost. WIEIAD videos function as one of these new monoculture moments. The format is instantly recognisable regardless of the creator. The visual grammar is shared. Even the critique of WIEIAD content has become its own recognisable genre, with registered dietitians and body-positive advocates building entire platforms around calling out problematic videos. Everyone is participating in the same conversation, even if they’re on opposite sides of it.

But while WIEIAD content creates a sense of shared culture, it also keeps us from making a genuine connection: we’re watching people eat rather than eating with them. The closeness is simulated, the intimacy is parasocial. We feel we know these creators, but they don’t even know that we exist.

What Comes After the What

What is the alternative to WIEIAD videos? Simply telling people to stop watching seems both naïve and insufficient. The hunger for these videos isn’t about food at all.

Some creators are experimenting with different approaches. With content that disrupts stigma, like people with ARFID trying new foods, neurodivergent creators discussing the meals they make when they feel overwhelmed. The key difference in these alternative approaches is intentionality. They deliberately disconnect food choices from appearance goals. They avoid body checking and keep things realistic, flexible and varied.

But even well-intentioned content faces the same fundamental challenge: it’s still operating within a system designed to create comparison and to keep users scrolling. The problem might not be WIEIAD content. The problem might be asking social media to meet needs it was never designed to fulfil.

The Meal We’re Not Eating

We watch because we’re hungry: we’re hungry for connection, for guidance, for the fantasy that there’s a simple set of rules that will make everything easier. WIEIAD content promises to provide those rules. Eat these specific things in this specific way at these specific times, and you too can be thin, energetic and in control.

The lie isn’t in the individual videos themselves. Most creators genuinely believe they’re sharing something helpful. The lie is in the system that strips eating from its context: the social bonds formed over shared meals, the pleasure of satisfying genuine hunger. And it is replaced by an endless scroll of images and videos that can never satisfy.

Perhaps the most radical response to WIEIAD culture isn’t to create better content or develop more mindful viewing habits. Perhaps it’s to close the app entirely and simply eat something without documenting it, without justifying it, without performing it for an audience. To remember that some experiences needn’t be optimised, aestheticized, or shared. That hunger is meant to be satisfied, not curated.

But that, of course, is much harder than it sounds when the algorithm already knows exactly what you’re craving, and it’s queued up the next video before you’ve even realised you’re still hungry.